Introduction

The coreboot porting efforts of the Gigabyte MZ33-AR1 are coming to an end. We have completed the AMD Turin SOC silicon porting already. All that is left to do:

-

Task 5. Platform-feature enablement:

- Milestone d. Board-specific IPMI commands

-

Task 7. Community tooling contributions

- Milestone d. Extend amdtool for Phoenix & future SoCs

-

Task 8. Upstreaming & community merge

- Milestone a. Code clean-up & internal review

- Milestone b. Initial patch series to coreboot Gerrit

- Milestone c. Review-cycle iterations & merge

- Milestone d. OpenSIL contribution & merge

And of course a Dasharo release, which is planned in the beginning of Q1 2026. The Gigabyte MZ33-AR1 will follow similar steps as the ASRock SPC741D8/2L2T, i.e. there will be reference builds in our shop including Dasharo Pro Package for Servers.

If you haven’t read previous blog posts, I encourage you to read them in case you have missed some.

Board-specific IPMI commands

IPMI stands for Intelligent Platform Management Interface and is a standardized interface for communicating with the Baseboard Management Controller (BMC) on a server platform. It is often used by BIOS and system admins to control the server. Despite the interface being well-described in its specification, OEMs often tend to extend the standard command set with their own specific commands for board-specific needs. For example, Supermicro servers implement their own command set to configure the BIOS version and BIOS build date in the BMC graphical UI, or a special command is sent to start the hardware monitoring and fan control. Commands for setting the BIOS version and build date are already available in coreboot. We hoped the BIOS information would be delivered to BMC on the Gigabyte MZ33-AR1 in a similar fashion.

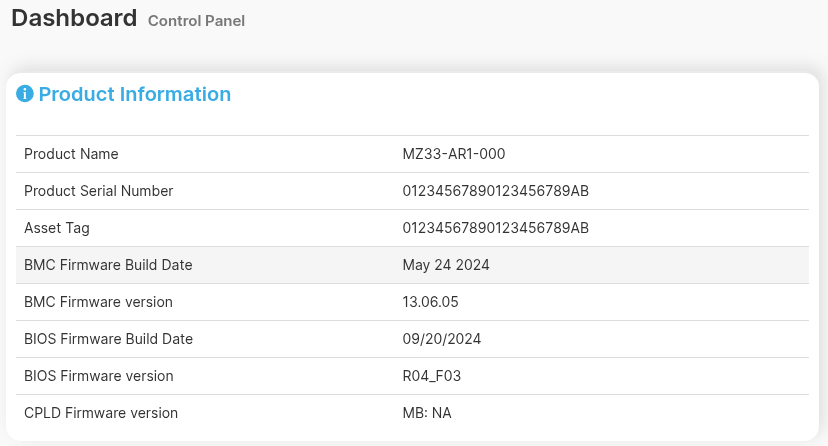

Throughout the whole project lifetime, we had no issues with fan control. After a minute or two, the BMC slows down the fans automatically according to the policy set via the BMC graphical UI. However, no matter what coreboot firmware version we flashed via the BMC graphical interface, it was never updated in the dashboard view:

So there had to be some IPMI command that updates the BIOS version and build date in BMC. After a very long analysis of the vendor firmware behavior, we did not manage to locate the exact command that would allow us to set the BIOS version and build date to match coreboot information, like the Supermicro driver does. Instead, we found only some commands to send Ethernet MAC addresses to the BMC and a command to send a huge buffer of 64K blocks to the BMC via the BMC VGA device MMIO resource. This mechanism exceeds the complexity of Supermicro driver present in coreboot and even the complexity we tried anticipate. While the Gigabyte firmware uses the standard IPMI KCS protocol to communicate with BMC, still the devil is in the details. I.e. what command bytes and data bytes should be sent, why, when and what are they responsible for. We have never seen such an implementation of BIOS to BMC communication using BMC VGA device MMIO. Sending 64K blocks over IPMI KCS interface is not efficient, that is why the VGA MMIO space was used for that probably.

Trying to locate all the data that is sent via this mechanism proved to be very difficult and would be impossible to finish in the time we allocated for this effort. Some of the data is acquired externally and some is created right before sending it. While we will share our findings here, it does not seem worth to pursue the proper implementation of Gigabyte’s IPMI specifics for interoperability. The implementation would probably not be usable for any other vendor of server boards. Instead, we wish to switch to the OpenBMC in the future and use standardized, open methods for BIOS to BMC communication.

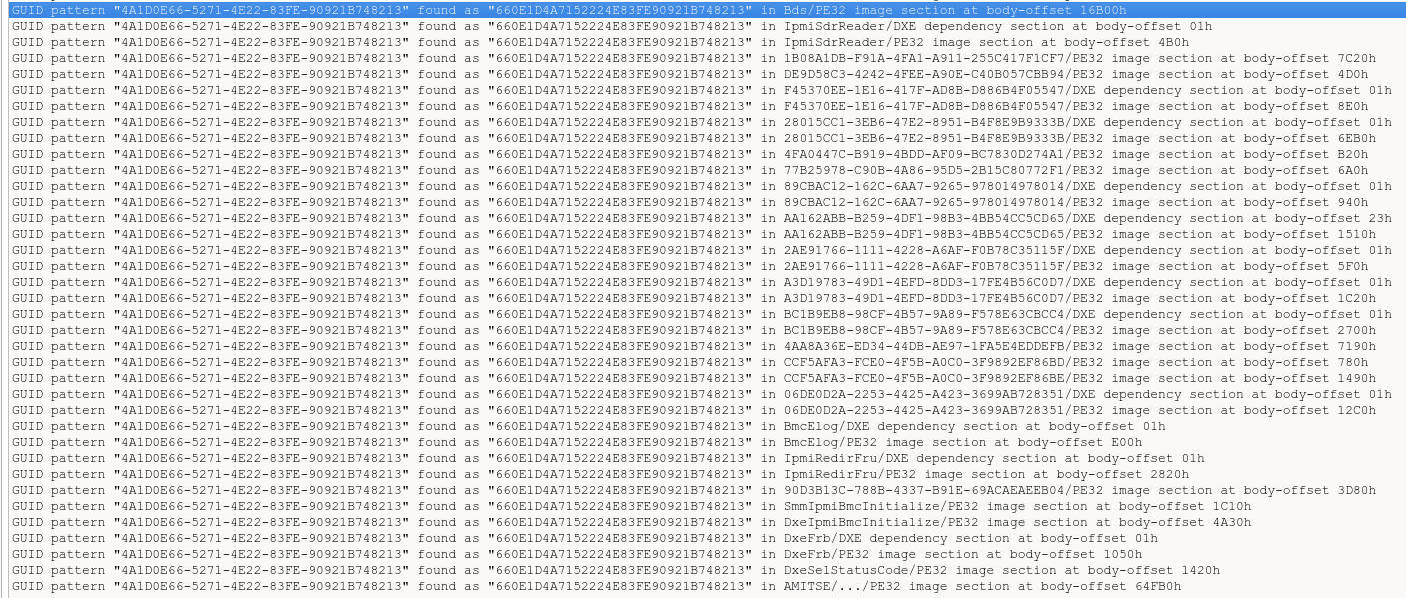

When approaching the analysis of server IPMI, one may simply check the

firmware binary for the occurrences of IPMI transfer protocol

GUID.

It runs out the AMI, company behind the Gigabyte’s BIOS, uses the same GUID

for IPMI transport protocol, as the public edk2-platforms IPMI driver:

4A1D0E66-5271-4E22-83FE-90921B748213. By looking at the modules which

include this GUID, we can pinpoint places where the BIOS to BMC communication

happens via IPMI:

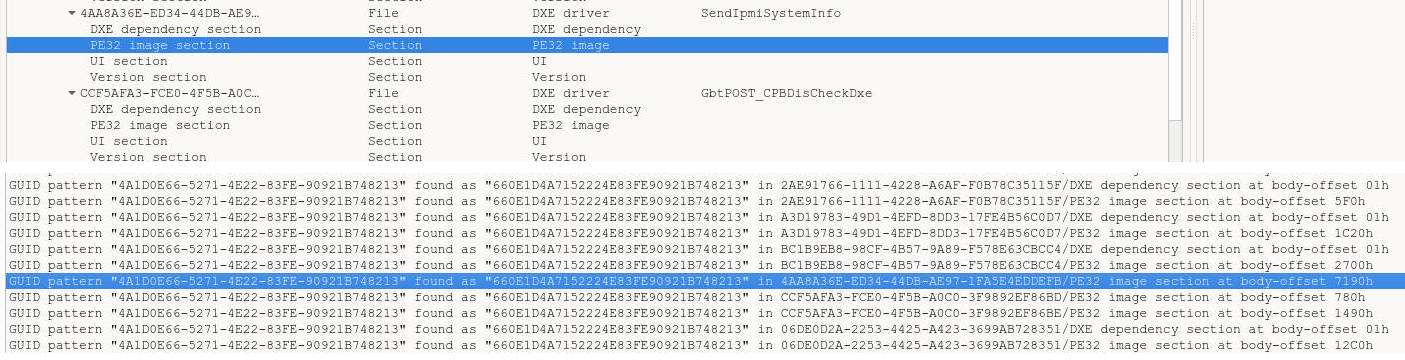

There are couple of such modules, where this protocol is used (search gives

doubled results, because the ROM is a dual image for Genoa and Turin, this is

just an excerpt). To filter out modules, which aren’t likely of our interest,

one may look at the UI section to match the module’s purpose with what you are

looking for, such as SendIpmiSystemInfo:

After analyzing this module, we found out that the system information is send in the 64K block via BMC VGA MMIO space. The transaction starts with an IPMI command sent in the same manner as in edk2-platforms, but the arguments are as follows:

- 2nd arg: NETFN 0x2e

- 3rd arg: LUN 0

- 4th arg: command 0x21

- 5th arg: command data: 32bit value for subcomamnd(?) 0x0a003c0a

- 6th arg: command data size 4 bytes

- 7th arg: response buffer address

- 8th arg: response buffer size 32 bytes

This seems to be some kind of indicator of the transaction sending system

information over VGA MMIO space. Then the data is coped to offset 0x10000 of

the VGA MMIO BAR 1 (VGA PCI offset 0x14 resource). The current offset of data

(if larger than 64K) is written to offset 0xF004 of the BAR 1 and an integer

1 is written to offset 0xF000 of BAR 1. After the data is coped another IPMI

command is issued to finalize the transaction and probably let the BMC consume

the data from VGA device:

- 2nd arg: NETFN 0x2e

- 3rd arg: LUN 0

- 4th arg: command 0x21

- 5th arg: command data

- 6th arg: command data size 10 bytes

- 7th arg: response buffer address

- 8th arg: response buffer size 64 bytes

The command data is as follows:

- 32bit value for subcomamnd(?) = 0x0b003c0a

- 2 bytes with size of sent data

- 2 bytes with size of sent data minus header size of 34 bytes

- two zero bytes: 0x00 0x00

The data buffer that is copied to the BMC VGA BAR 1 space has the following content (may not be 100% accurate):

- SMBIOS 3.0 entry point structure (described in SMBIOS specification section 5.2.2, 24 bytes)

- whole SMBIOS data pointed by

Structure table addressfield of SMBIOS 3.0 entry point structure (size indicated byStructure table maximum sizefield of SMBIOS 3.0 entry point structure) - Disk information starting with

_HD_andRV11signatures (16 bytes) followed by two buffers of variable size copied:- one containing SATA controller port information (structure of data unknown)

- second probably connected disk detailed information (structure of data unknown)

- CPU information starting with

_CPU_signature (72 bytes)- The CPU information includes mostly a subset of feature bits extracted with CPUID instruction, number of processors

- Memory information (64 bytes) starting with

_MEM_signature- There isn’t any buffer copied here, BMC maybe retrieves the memory data by itself using I2C/I3C/SMBUS connection

- Network controller information starting with

_LAN_signature followed by a buffer of data (structure of data unknown) copied - Mainboard(?) data (32 bytes) starting with

_MDATA_signature followed by 3 buffers of data of variable size (structure of data unknown) copied - Ending header (34 bytes) starting with HEADER signature

- The header contains the size of the header and sizes of each information block sent earlier

Everything besides the SMBIOS data is custom and deciphering what should be placed in the buffers listed above would be tremendous amount of work. As our wish is to run OpenBMC on this platform eventually in the future, it does not make much sense to pursue the analysis further to uncover every possible detail. Even if we could possibly sniff the eSPI bus which connects the BMC to host CPU and transmits the IPMI commands to BMC, we would not be able to peek into VGA MMIO space easily to uncover the data sent to BMC.

But we learned some lessons from that analysis:

- With both OpenBMC and proprietary BMC, the host–BMC interface is IPMI KCS, a documented standard.

- With OpenBMC anyone can read the code, verify how it implements the protocol, and test it against the spec.

- On proprietary systems the vendors are implementing sets of custom OEM IPMI commands and opaque interfaces: you cannot easily see what metadata is exchanged, what commands exist, what controls are possible, or what security assumptions are made. Vendors deviate from a visible norm without visible reason.

With open implementation like OpenBMC, there is a strong focus on standardized implementations (IPMI, PLDM, Redfish). The expected behavior (messages, states, error handling) is well documented and test harnesses, and analyzers are provided to ensure the security of the implementation.

This concludes the IPMI commands porting, which fulfills the following milestone:

- Task 5. Platform-feature enablement - Milestone d. Board-specific IPMI commands

Phoenix support in amdtool

In the previous blog post, we introduced the amdtool - a utility for dumping

useful data for coreboot porting. Back then, it only supported AMD EPYC Turin

CPUs. Now we have extended the tool to dump data from Phoenix desktop CPUs and

tested it on MSI PRO B650M-A with a Phoenix CPU (AMD Ryzen 5 8600G). Example

output from the utility can be found

here.

The relevant patch implementing the support for Phoenix CPUs in amdtool has

already been merged in upstream

coreboot. Most things are

generic and could stay intact. The only parts that required some changes were

the IRQ mapping (because the available devices on desktop and server platforms

are a bit different) and the GPIOs. GPIOs naturally change between

CPUs/microarchitectures, so this is not a surprise. The difference in GPIOs is

also a result of different CPU socket (Turin SP5 vs Phoenix AM5).

This concludes the community tooling contributions, which fulfill the following milestone:

- Task 7. Community tooling contributions - Milestone d. Extend amdtool for Phoenix & future SoCs

Upstream status

Doing open-source also means contributing and upstreaming your efforts. Throughout the whole project lifetime, we did the development directly on upstream sources, sent patches along the way, and replied/fixed the patches whenever possible.

Quick summary of the patches:

-

coreboot:

- Patch search query

- Note: statistics may change as the work is constantly being done on the patches

- 84 patches (6 of them already merged)

- difference:

132 files changed, 5600 insertions(+), 589 deletions(-)(plus changes from initial board structure41 files changed, 3218 insertions(+))

-

OpenSIL:

- PR: Fix build for coreboot

- PR: xPrfGetLowUsableDramAddress workaround and SATA support

- PR: CCX AP launch fix

- PR: xUSL/Nbio/Brh: Fix interrupt routing and swizzling

- PR: xSIM/SoC/F1AM00: Add SDXI TP1 initialization

- PR: Turin PI 1.0.0.7

- PR: xPRF/CCX/xPrfCcx.c: Remove unused NumberOfApicIds variable

- 7 pull requests (6 of them already merged)

- difference:

86 files changed, 4049 insertions(+), 990 deletions(-)

One may say it took roughly 13k LOC added and/or changed to add support for non-existent microarchitecture in coreboot. Obviously, this does not count the tremendous work of AMD and partners to create OpenSIL for Turin (and also Genoa) CPUs. For comparison, the initial OpenSIL commit adding Turin support is 108K LOC, so our changes are roughly ~3.7% of the whole OpenSIL codebase. We can’t compare it to Intel FSP, because it is not public, but we may try to compare how much code is required in a framework to support a new microarchitecture. For example, MeteorLake support in Slim Bootloader was nearly 90K LOC. However, most of the code is very similar to other microarchitectures and is probably copied over with microarchitecture-specific changes. This shows how well coreboot is at designing generic code for given silicon vendor (5.6K out of 90K is ~6.2%).

All patches have been just refreshed and rebased, and we will be working with community towards merging all of the changes in the upstream repositories.

This concludes the upstream efforts, which fulfill the following tasks and milestones:

Task 8. Upstreaming & community merge

- Milestone a. Code clean-up & internal review

- Milestone b. Initial patch series to coreboot Gerrit

- Milestone c. Review-cycle iterations & merge

- Milestone d. OpenSIL contribution & merge

Summary

The journey maybe was not that long, but we are glad you stayed with us till the end and were not scared by the extensive explanations of complex technical aspects. We hope that our explanations have let you grasp the firmware realm, expanded your knowledge, even if just a bit, and that you enjoyed the blog series. Stay tuned for the incoming Dasharo release compatible with Gigabyte MZ33-AR1.

Huge kudos to the NLnet Foundation for sponsoring the project.

While this is a last blog post of the series and we have a booting solution on AMD Turin EPYC processors and the Gigabyte MZ33-AR1, the OpenSIL is still far from its proprietary/closed source counterpart AGESA, used by Independent BIOS Vendors. OpenSIL does not implement non-x86 initialization, like SMU or PSP (we had to add SMU initialization to get CPPC working anyways). PSP is the center of security features on AMD platforms. It is responsible for memory encryption, virtualization encryption features and other security features, such as ROM Armor. In the terms of security the open-source AMD Turin support is far from complete. But maybe we will have a chance to fill that gap with the generosity of NlNet in the future project funds, who knows.

Unlock the full potential of your hardware and secure your firmware with the

experts at 3mdeb! If you’re looking to boost your product’s performance and

protect it from potential security threats, or need support in enabling your

hardware platform in various firmware frameworks, our team is here to help.

Schedule a call with

us

or drop us an email at contact<at>3mdeb<dot>com to start unlocking the

hidden benefits of your hardware. And if you want to stay up-to-date on all

things firmware security and optimization, be sure to sign up for our

newsletter: